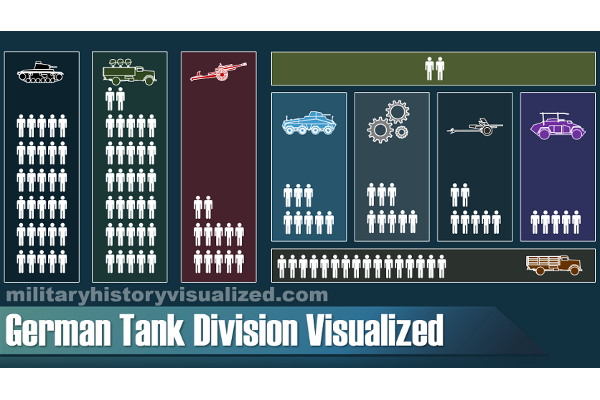

Men & Equipment

Probably one of the most iconic references to the Battle of Britain is the quote ”Never was so much owed by so many to so few”, hence let’s start with the numbers of men and equipment:

During the height of the battle in August 1940 the Fighter Command had around 1380 and the Luftwaffe 870 fighter pilots.

In terms of planes the British had 1000 fighters, which is around the same number as the Luftwaffe.

Yet, only 700 of the British fighters were operational, whereas 800 of the Germans.

The main part of the Fighter Command planes were Hurricanes with about 55 % of the operational fighter aircraft whereas the Spitfire only reached around 30 %.

The German Luftwaffe used only one Single Engine Fighter the Bf109 (of the E-Series/Variant.)

Organization

The Royal Air Force and the Luftwaffe were organized differently. The RAF used a functional approach having a command for bombers, coastal aircraft, reserves, training and fighters. Furthermore, Fighter Command had operational direction over the Anti-Aircraft Command, which was part of the British Army.

The Luftwaffe was organized in so called “Luftflotten” literally meaning “Air Fleets” that used a mix of fighter, bomber and other aircraft.

Yet, the organization wasn’t a major problem for the Luftwaffe. In Poland and the Battle of France the Luftwaffe achieved air superiority in a short amount of time. Thus, it had little experience in escorting and especially defending large formations of bombers. Furthermore, the Luftwaffe was first and foremost a tactical-oriented air force for providing close support to the army, but it was not suited for strategic operations. Thus the Luftwaffe went into a battle it was neither experienced, trained nor built for against the RAF, which also had a well-organized defense system. (So let’s take a look at it.)

British Command and Control System

Fighter Command was divided into 4 Groups and these were divided into individual Sectors with their sector station, whereas sector station is a fancy name for airfield. This hierarchy also reflected how information was transferred.

When enemy aircraft were detected by radar the Fighter Command headquarters was informed. This information was relayed to the Group HQs and individual sector stations. The Group HQs decided which sectors were activated, whereas the sector commanders decided on which squadron would be sent into combat.

Since radar stations could only provide information on planes flying over the sea, once planes were flying inland further information was provided by trained volunteers to the Observer Corps, which relayed it directly to the sector stations, who reported to the Group HQ.

Radar

A central part of this system was the so-called Radar, which is an acronym for “Radio Detection and Ranging”.

The Chain Home System had 21 radar stations that could detect the range and altitude of planes up to a 200 mile or 320 km radius, but the average was only 80 miles or 130 km. Aircraft flying below 1000 feet or 300m could not be detected by this system. To detect low flying planes the Chain Home low station system was used which had only a range of about 30 miles or 50 km.

Although this system seems flawless in theory in practice there were many problems, e.g., radar stations being out of order due to upgrades and inaccurate data from the Observer Corps.

Also relaying the radar information to the squadrons took at least 4 minutes, whereas a German squadron could cross the Channel in about 6 minutes.

Another source of viable information was signal interception. Decrypted enigma traffic usually couldn’t be provided fast enough to help intercept raids, but due a weak low-level-radio discipline on the German side there was usually a steady information about destination and origin of enemy squadrons.

This system allowed Fighter Command to choose when and where to attack. Something the Luftwaffe Command never faced before and even more important probably never fully realized throughout the whole Battle.

Notes on Accuracy

The numbers are mostly from Overy (see sources). Often those numbers are at the beginning or end of the month, but usually for different dates for the German and British forces. For simplicity I only state the month. This video is intended to give a clear and short overview, hence certain details can’t be included.

Sources

Books

Overy, Richard: The Battle of Britain – The Myth and the Reality (amazon.com affiliate link)

| amazon.com | amazon.co.uk | amazon.ca | amazon.de |

Disclaimer amazon.com

Bernhard Kast is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to amazon.com.

Disclaimer amazon.co.uk

Bernhard Kast is a participant in the Amazon EU Associates Programme, an affiliate advertising programme designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.co.uk.

Disclaimer amazon.ca

Bernhard Kast is a participant in the Amazon.com.ca, Inc. Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.ca.

Disclaimer amazon.de

Bernhard Kast ist Teilnehmer des Partnerprogramms von Amazon Europe S.à.r.l. und Partner des Werbeprogramms, das zur Bereitstellung eines Mediums für Websites konzipiert wurde, mittels dessen durch die Platzierung von Werbeanzeigen und Links zu amazon.de Werbekostenerstattung verdient werden können.

Online Resources

The RAF Fighter Control System